What I wanted was to write, and I resolved to read this marvelous work and be illuminated by all its radiance.

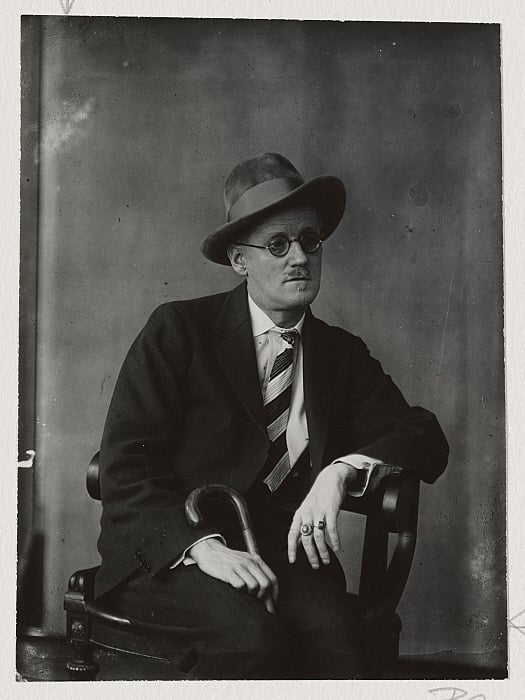

The word “modernism” evoked in me a vague notion of machines, futuristic and shiny, and when I read about the tower that Stephen inhabits at the beginning of the book, I imagined some sort of medieval world of turreted castles, though with cars of the 1920s and airplanes, a place populated by young men reciting works in Latin and Greek in other words, something very remote from the world in which I resided, with its quaysides and fishing boats, its steeply rising fells and icy ocean, its fishermen and factory workers, TV programs and pounding car-audio systems. That ambition had prompted me to subscribe to a literary journal, and in one of the issues that came in the mail there was a series of articles on the masterpieces of modernism - among them Joyce’s novel “Ulysses,” which he published six years after “Portrait,” and which also featured the character of Stephen Dedalus. The first time I heard about James Joyce, I was 18 years old, working as a substitute teacher in a small community in northern Norway and wanting to be a writer.

Joyce’s novel remains vital, in contrast to almost all other novels published in 1916, because he forcefully strived toward an idiosyncratic form of expression, a language intrinsic to the story he wanted to tell, about the young protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, and his formative years in Dublin, in which uniqueness was the very point and the question of what constitutes the individual was the issue posed. What appeared at the time to be unprecedented about the novel seems more mundane to us today, whereas what then came across as mundane now seems unprecedented.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” Its genesis was long and tortuous - Joyce began writing his novel in 1904 - and the road to its canonisation as one of the seminal works of Western literature was not short either: The reviews spoke of the author’s “cloacal obsession” and “the slime of foul sewers,” comments that seem strange today, insofar as it is the subjective aspect of the book, the struggle that goes on inside the mind of its young protagonist, that perhaps stands out to us now as its most striking feature.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)